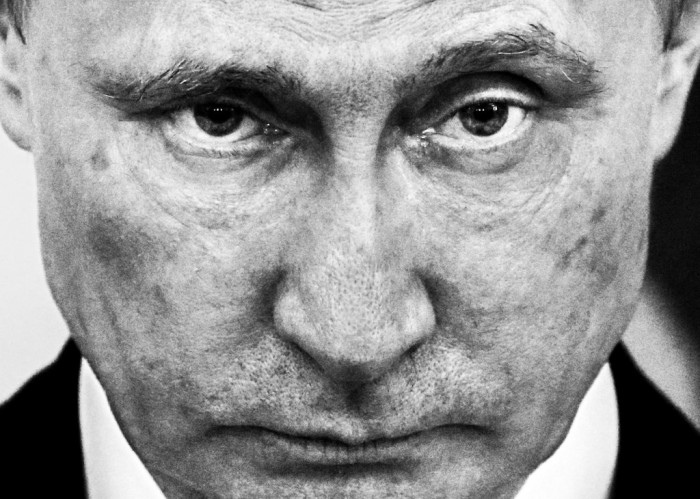

The Putin I Knew; the Putin I Know

I met Vladimir Putin and trusted him in the early 1990s, when he was deputy mayor of St. Petersburg. Now that he’s Russia’s president, he’s different. He’s no friend of democracy.

By Franz J. Sedelmayer

Mr. Sedelmayer has recently taken up residence in the United States.

President Vladimir Putin of Russia celebrated the New Year by having an American tourist, Paul Whelan, arrested as a spy. Mr. Whelan was in Moscow to attend a wedding. But Mr. Putin needed a hostage as a potential trade for a Russian woman with Kremlin connections — Maria Butina, who had pleaded guilty of conspiring with a Russian official “to establish unofficial lines of communication with Americans having power and influence over U.S. politics.” So Mr. Putin grabbed Mr. Whelan, who has not been released.

Of course Mr. Putin did that. I’ve known him since the early 1990s. As a businessman in St. Petersburg, I spent scores of hours with Volodya, as he was known in those days, while he was the city’s deputy mayor. He sat in my headquarters on Stone Island as we conversed, in the almost-perfect German he likes to speak, over beer and Bavarian food. My trust in those early days was based on the fact that he acted rationally and appeared to be sincere in his interest in St. Petersburg. He didn’t take bribes, but he did cover for those who did, including his bosses — Mayor Anatoly Sobchak and later President Boris Yeltsin. Mr. Putin signed the registration papers for my security company and personally registered them. He advised and counseled me. He helped me expand my business. And at his request, I built, trained and equipped St. Petersburg’s first Western-style K.G.B. SWAT team, in preparation for the 1994 Goodwill Games there.

From our conversations in 1992, I realized that Mr. Putin understood that it was not the West, but the Soviet socialist system that was responsible for the social and economic downfall of the Soviet Union. Indeed, when we spoke about my native Germany, there was every indication that he had accepted German reunification as inevitable once the Berlin Wall came down. It was after he became president in 2000 that he worried increasingly about Russia’s political and economic failures and bemoaned a lack of what he considered proper respect from the West — and turned Russia inward with ideology and religion as tools.

For me, a different moment of change came in 1996, when my company and the headquarters in which I’d invested more than $1 million was expropriated by President Yeltsin. Volodya shrugged and told me there was nothing he could to do to help. And I began watching him metamorphose from a minor bureaucrat into the authoritarian four-times-elected president of Russia. I can tell you the Mr. Putin that Americans read about today is nothing like either the Mr. Putin I knew at first or the one I know now.

The Mr. Putin I know is in many ways similar to President Trump. Like him, Volodya makes decisions based on snap judgments, rather than long deliberation. He’s vindictive and petty. He holds grudges and deeply hates being made fun of. He is said to dislike long, complicated briefings and to find reading policy papers onerous.

Like Mr. Trump, the Mr. Putin I know reacts to events instead of proactively developing a long-term strategy. But in sophistication, he is very different. A former K.G.B. officer, he understands how to use disinformation (deza), lies (vranyo), and compromise (kompromat) to create chaos in the West and at home.

A couple of months ago, I moved to the United States and set up a company to help others who have lost their businesses or assets, or had them stolen. I had by then spent two decades suing the Russian Federation — not just in Russia but also by laying claim to Russian government property in Sweden and Germany — and emerged as the only party ever to collect damages from the Russian Federation.

That long, long march convinced me that neither Mr. Putin nor Russia was my friend. Like me, Western leaders had trusted Mr. Putin. But they did not understand that to him, politeness and friendship were often signs of weakness, not friendship. More than anything, he wants to be taken as an equal or a superior, trying to destroy anything with which he cannot compete.

And yet, living in America, I couldn’t help noticing that the media there are reticent when it comes to telling its audiences that Mr. Putin’s Russia will never be democracy’s friend. Volodya’s Russia wants to divide and to destroy democracies. To that end, Volodya employs his Kremlin apparatus, notably the shadowy and largely unknown Presidential Property Administration of the Russian Federation, or UdPRF.

The UdPRF’s black budget is in the billions of rubles. It controls perks dispensed to obedient Kremlin apparatchiks, but also covert action programs of the sort that resulted in the Trump dossier assembled by Christopher Steele in 2016. It’s certain that under the Mr. Putin I know, all of Russia’s varied intelligence agencies will continue to practice deza, vranyo, and kompromat operations against the United States. And personnel from Russia’s main intelligence agency, the F.S.B., and its military intelligence agency, the G.R.U., will be involved in more attacks against and murders of Russian dissidents and opponents of Mr. Putin living in the West. To the Mr. Putin I know, borders mean nothing.

A couple of months ago Volodya tried — luckily, he failed — to insert a crony as head of Interpol, the international police organization, presumably so he could turn it into his personal posse. Of course he did. Corruption is in Russia’s DNA, as it is in Mr. Putin’s.

Something else I’ve discovered since moving is that many of America’s Kremlin-watchers don’t understand that Mr. Putin is running scared these days. His recent election may have been guaranteed; his future is anything but.

Why? Because Volodya has no one watching his back. Mayor Sobchak and President Yeltsin hired and promoted him because of his personal loyalty, but both are long dead. The Mr. Putin I knew back then allowed his superiors to accumulate huge wealth, and then he shielded them from indictment. He built a protective wall around Mr. Sobchak even as the mayor was caching millions of dollars in Paris. Later, as head of Mr. Yeltsin’s F.S.B., Mr. Putin quashed an investigation of the Yeltsin family by the prosecutor general at the time, Yuri Skuratov, by vouching for the authenticity of a fuzzy video of a man said to be Mr. Skuratov in bed with two prostitutes. And in his first hours as acting president of the Russian Federation on Dec. 31, 1999, Volodya wrote a decree that pardoned Mr. Yeltsin and his family from any criminal charges.

But there are no such decrees in Volodya’s future. It has long been rumored that he has a huge fortune stashed away. But if that is true, it is likely held by friends, associates or even some of the criminals Mr. Putin has made filthy rich.

So, my question is: When Volodya finally leaves power, will those filthy-rich friends, associates and co-conspirators give him back any of those billions?

Somehow, I don’t think so. I’ve lived in Russia. Sharing’s not the Russian way.

Franz J. Sedelmayer is the chief executive officer of MARC, the Multinational Asset Recovery Company, and the author of “Welcome to Putingrad.”

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/04/opinion/the-putin-i-knew-the-putin-i-know.html