UNDERSTANDING CIRCASSIAN FOLKLORE

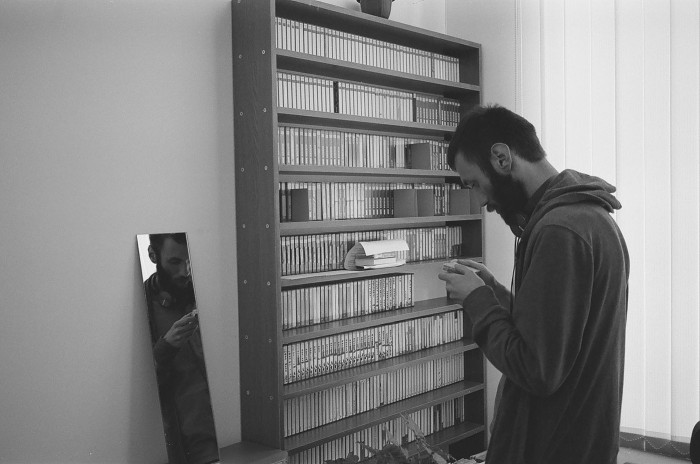

Producer Bulat Khalilov, together with his label Ored Recordings, studies and documents traditional music of the Caucasus.

- TEXTGrigor Atanesian

- PHOTOGRAPHYAlisa Schneider

Bulat Khalilov documents traditional folk music in remote villages of the Caucasus, gathering material for his label Ored Recordings, and furthering his understanding of folklore. The expeditions around the region, carried out by Khalilov and the Moscow-based electronic musician Moa Pillar, have become the basis for the film “Bonfires and Stars,” shot in 2015 by director Sasha Voronov and Stereotactic studios.

Bulat Khalilov was born in Nalchik. His father was a builder, and his mother was a teacher. There, in the Kabardino-Balkaria region, the Circassians or “Adyghe” people (as they call themselves) live to this day, representing one of the indigenous peoples of the North Caucasus. As a child Khalilov would often visit relatives in the countryside, where the Circassian language was still spoken, but he recalls these trips with some bitterness: “I knew the mother tongue but never practiced it, so my relatives would laugh at my mistakes. Because of their mockery and my own adolescent negativity, I conceived a hatred of my own culture.”

Like the majority of post-Soviet teenagers, Khalilov grew up on Western music, and was one of the first in his town to download music, listening to the “noise” and “industrial” genres. He entered the faculty of applied IT after graduation, but soon switched to the journalism faculty and began working as a music reviewer for the local magazine.

When Khalilov met musician Timur Kodzokov a few years later, they decided to go into production together and started looking for local groups that would be in keeping with their aesthetic interests. However, the active rock and punk scene of 1990s Kabardino-Balkaria fell into decline toward the end of the 2000s. Yet, hand-in-hand with their disappointment in modern music came an interest in Circassian folklore, fostered under the influence of French director Vincent Moon, the creator of more than 300 films about music groups from R.E.M. to Arcade Fire. Moon had begun researching traditional music in 2010, and when the director set off for Russia, Khalilov offered to help organize his trip to the Caucasus.

When Moon arrived in Kabardino-Balkaria in 2012, Bulat worked as producer on his film and documented a series of Moon’s projects: “OKO: Carnets de Russie,” with the subheading “Folk music of the ethnic minorities of Russia.” He was responsible for almost everything – from funding to liaising with local musicians. “Vincent and I had a mutual understanding,” recalls Khalilov. “I soon realized, as he did, that folk is the same as rock music. It’s essential to show the kids of today that their grandma from the countryside is just as cool as Beyonce. In an interview at that time I said that the principles of folk music fully correspond with those of experimental music. But I don’t think like that anymore.”

Khalilov and Kodzokov started to study Circassian folk artists and realized that, together with Moon, they had documented a large amount of late, Soviet folk music which wasn’t particularly interesting in terms of music or research.

They had, however, recognized Zamudin Guchev as one of the real leaders in the world of Adyghe folk music. In 2005 he founded “Zhyyu,” a vocal ensemble dedicated to authentic, devotional songs. Khalilov was a guest of Guchev in a village below the town of Maykop, where he was reintroduced to the Circassian language after a long lapse. Impressed by the quality of a recording of the ensemble, he delved further into the principles of Circassian-Adyghe national music, and began to revisit his own native culture.

Songs play an important role in traditional Adyghe society, and each existing genre fulfills its own designated function. Tales of heroes constitute the basis of Circassian folklore. Since the Adyghe people never created their own written literature, they preserve and hand down the history of their people via such songs. Humorous fables, pagan creation tales and Muslim spiritual music exist side by side. The Zachiry genre, for example, is devoted to the foundation of the Muslim faith and praise of the prophet Muhammad. The Adyghe tradition of song relies upon group performance: One person sings the narrative line while the others sing the refrain or “under-echo” – translated into Circassian as “Zhyyu.”

…………

Khalilov soon founded Ored Recordings, named after the Circassian word “ored” (song). One of the label’s first releases was a recording of a traditional “Dzhegu” (festive gathering), an important part of Adyghe culture. In ancient times these celebrations happened for various reasons and could last for several days with ceremonial songs and dances, play fighting, horse races, and other competitions. A key figure of the festivities and the “master-of-ceremonies” would be responsible for singing the narrator part in the “dzheguako.” The role falls somewhere between that of an old Scandinavian skald, a pagan shaman, and a court jester.

The release was put together according to the modern Western music model with an intro and defined track list. But in subsequent recordings Khalilov and Kodzokov abandoned such editing, attempting to replicate the experience itself. Through self-funding and the help of friends, they have recorded and released 12 further records, which include the traditional songs and instrumental music of Circassians, Abkhazians, Pontic Greeks, Dargins, Chechens, Laks, Kalmyks, and Caucasian Turks. These cultural journeys include towns and villages in Dagestan, Adygea, North Ossetia, Kabardino-Balkaria, Chechnya, and also parts of neighboring Abkhazia and Azerbaijan. Although the Circassian-Adyghe folk culture is the most interesting and personal for Khalilov and Kodzokov, they stress that the project is devoted to traditional music as a whole, without any attachment to one specific culture.

The label’s initial releases sought to tackle the generally negative attitude toward folk artists, and avoided approaching folklore as a subject of research. “We didn’t want to prepare for our expeditions, we thought it was unnecessary. I remember when we were in Dagestan we went up to a group of performers and asked: ‘Why do you still sing?’ I realized I looked stupid.” They now acquaint themselves with the appropriate academic literature before each expedition. “At first we approached folk as just some kind of cool music. But research doesn’t detract from the quality of our recordings or their authenticity,” says Khalilov.

This approach to subject research may be new among Russian folklorists, but Ored Recordings can look to such examples as Smithsonian Folkways – the sound-recording department of the Smithsonian Institute in the United States. According to Smithsonian Folkways, their aim is to simultaneously research, preserve, and popularize traditional music.

Khalilov is quick to say that Ored allows its recordings to find their own audiences: “One mustn’t put popularization at the forefront because folk music is usually tedious for the mass audience and then a process begins to create some kind of hybrid between folk and pop music, which is exactly what ‘World Music’ is.” He believes that good music needs no advertisement: “No one tried to popularize jazz, did they?”

The more Khalilov and Kodzokov learn about folklore, the less they wish to experiment with it. But their approach is not an attempt toward some kind of original purity, which many Adyghe cultural figures seek. A large part of Adyghe history is defending their independence and even actively conquering neighboring territories. Circassian Mamluks, for example, founded a sultanate in modern Egypt in 1215 and ruled over the people there for three centuries. But at the start of the 19th century, those who remained in the Caucasus fell victim to Russian expansion, which resulted in the mass deportation of the Adyghe people to the Ottoman Empire. During the Soviet Union, the Adyghe nation was separated and forcefully relocated – scattered across the republics of the Caucasus.

………

Nowadays in Circassian folklore, songs about Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks – some with Russian vocabulary – exist alongside the ancient legends. According to Bulat, foreign influences do not hinder the revival of a national culture: “The idea of a pure culture or nation is fascism. Indigenous elements often turn out to be alien influences. There’s nothing bad about this. Folklore is not a philosophy but a practice. The receptivity to influences is an indicator that the culture is still alive.”

With thanks to Stereotactic and Sasha Voronov for the use of video material.

With thanks to Tembolat Keref and Madina Pashtova for help with translation.

DoP Ruslan Fedotov, editing Alexander Pavlov, sound recording Vadim Kolosov, sound design Ivan Merkulov, CG Alexey Kurbatov, producer Alisa Schneider.