Sochi Once Again Epicenter of Russian-Circassian Conflict—But Circassians Register a Win

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 17 Issue: 100

For the third time in history, Sochi has become the epicenter of the conflict between Russians and Circassians. In 1864, it was the place from which tsarist forces exiled to the Ottoman Empire most of the Circassians who had resisted the Russian advance for more than 100 years. In 2014, on the 150th anniversary of those horrific events, which many characterize as an act of “genocide,” President Vladimir Putin organized the Olympics on precisely this spot. In response, Circassian activists in the North Caucasus homeland and in the diaspora organized for international action. They called attention to the crime itself as well as the Russian government’s failure to repent. Additionally, they spotlighted Moscow’s effective ban on allowing the Circassians to live in a common homeland and to permit the return from war-torn countries in the Middle East of the descendants of those exiled there. Now, in the last ten days, this southwestern corner of the Russian Federation has again witnessed a Russian-Circassian conflict after local activists put up a monument to the Russian soldiers that defeated the Circassians in the 19th century. However, following renewed protests from Circassians in the homeland and the diaspora, the Sochi authorities were compelled to remove the statue—a signal Circassian victory in a multifaceted struggle that shows no sign of being resolved anytime soon.

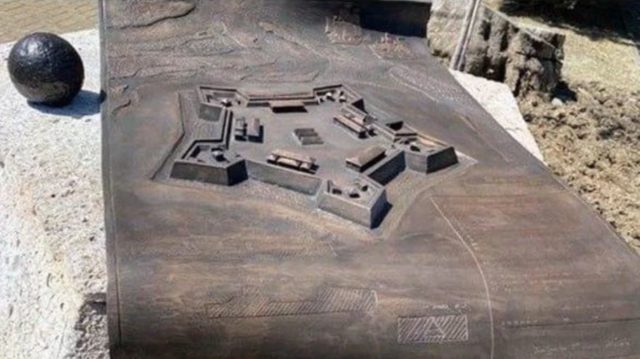

The latest act in Russia’s monument wars against non-Russians in general and the Circassians in particular (see EDM, May 27, 2014 and November 8, 2016) began at the end of May 2020, when Russian Orthodox and military activists, after more than a year of planning, erected a memorial at the corner of Marx and Krupskaya streets, in the Adler district of Sochi. The stone-and-metal monument venerated those tsarist troops who fought against the Circassians in 1837. Organizers said they had the blessing of the city authorities, who in fact had posted a statement on their webpage praising this civic action. But the page disappeared from the Sochi city website after the Circassian protests began; municipal officials now deny ever posting the statement of approval (Kavkazsky Uzel, July 4).

Not surprisingly, the new monument, featuring a metal cast of a Russian fort of the kind used to occupy the Caucasus, outraged Circassians. They viewed it not only as a direct insult to their nation but also as yet another indication that Putin is increasingly reverting to a policy of Russian imperialism and treating non-Russians under Moscow’s control as colonies. Circassian historians and activists immediately spoke out against the new marker. Ruslan Gvashev, one of their number, said that Sochi already had enough monuments dedicated to the Circassian war and that putting up more was only designed to show the power of Russia over numerically smaller groups like the Circassians. Many others echoed his words, including historian Khadzhimurad Donogo, who contended that putting up a new monument was “an unwise and illiterate policy” that would only further enflame hostilities among the peoples of the region. In turn, Dagestani scholar Zurab Gadzhiyev asserted that there could not be any “ethical basis for putting up such monuments” (Kavkazsky Uzel, July 4; Kavkazr.com, July 7).

These arguments and those of others led Circassians both in the North Caucasus homeland and the diaspora to draft an appeal to the Russian president and to collect signatures of support. This effort was coordinated by the Circassian Coordination Khase, including Rashid Mugu, Valery Khatazhukov, Aslan Shazzo, Alik Shashev and Murat Temirov. The letter called on the Kremlin leader to order the statue removed and compel the local authorities to apologize, warning that if that did not happen, ethnic tensions in the region would rise to a potentially dangerous level (Kavkazsky Uzel, July 5; Zapravakbr.ru, Justicefornorthcaucasus.info, July 7).

Possibly because of this warning and almost certainly because the Kremlin did not want to have an explosion in the North Caucasus spoil celebrations of its victory in the July vote on the constitutional amendments (see EDM, July 2), Moscow backed down in this case and ordered Sochi to do the same. Yesterday (July 8), first via a text message to the Kavkazsky Uzel news agency and then on its own website, the Sochi city authorities announced they had removed the monument, giving the Circassians a genuine and welcome victory (Kavkazsky Uzel, July 8). Media outlets in Moscow and in other parts of the Russian Federation, not to mention the Circassian diaspora, immediately picked up on the news, suggesting others will also conclude that resistance to such displays of imperialism can be effective (Ekho Moskvy, July 8; Bragazeta.ru, Capost.media, July 9).

It seems clear that officials in the Russian capital decided their Sochi subordinates had gone too far and needed to be reined in before producing the kind of disaster that would have far-reaching consequences. But it is also the case that this Circassian victory is not a final one and may not even be a turning point. Even as the monument on Marx and Krupskaya was removed, officials put up another one in the Adler district, to Russian saints (RIA TOP 68, July 9). At the same time, longtime Moscow allies within the Circassian community have continued to attack the campaign to encourage all Circassians to identify themselves as such in the upcoming Russian census; additionally, they criticized efforts to enable the return of members of the diaspora to their homeland as well as the restoration of a single Circassian republic in the Northwest Caucasus (Kavkaz Segodynya, July 6). Meanwhile, Moscow continued its efforts to destroy Circassian unity by means of an Operation Trust–style operation against the diaspora (Windowoneurasia2.blogspot.com, July 2). And the Russian government has sought to undermine this nationality’s Western support by attacking The Jamestown Foundation and others who speak out about the rights of the Circassians (Genproc.gov.ru, April 8; see Jamestown.org, April 9).

Both these Russian actions and Moscow’s retreat on the Sochi memorial, however, highlight that the Kremlin is increasingly worried about the unity and power of the Circassians. This nationality and their friends and supporters can see that too; as a result, they are not going to back down on any of their current efforts. Instead—and this is no small thing symbolically—Circassian activists have launched a counter-attack in the monuments war. This week, in the Turkish city of Eskişehir, they put up a memorial to those who fell fighting the Russians in the war between 1763 and 1864 (Natpressru.info, July 7). Quite clearly, neither they nor Moscow sees that struggle as only a historical question.