Circassia: The land, people, and brutal Russian genocide you’ve never heard of

Monday October 17, 2022

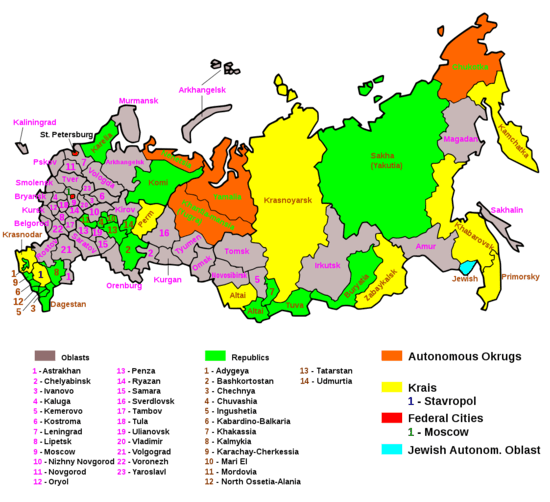

In an article today, Kos mentioned that he isn’t personally familiar with the all of the sundry Russian Republics, and neither am I… but I can give a little context to the group of them in the southwest corner. Adygea, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachay-Cherkessia (plus Krasnodar Krai, the yellow area surrounding squiggly little Adygea) all have to be considered together. This was once Circassia, homeland of the Circassian people.

Well, until the Russian Empire got involved, anyway. In 1763, Russia essentially declared that it was annexing Circassia. The Circassians… strongly disagreed, sparking one of the longest, bloodiest, most brutal conflicts that you’ve never heard of. The Russo-Circassian War lasted from 1763 until the final Circassian army was defeated in 1864. Yep, that’s 101 years of more or less constant warfare in the region, combined with relentless atrocity. The Russians declared the Circassians to be “subhuman”, “mountain scum”, and “untrustworthy swine” and that Circassia was a land of “bandits” and criminals. And I bet you can guess where this is going.

As Russia pushed into Circassia, they conducted a campaign of genocide and expulsion that would make that guy in Germany later on pretty proud. Starting in 1802, General Pavel Tsitsianov’s campaign in Circassia featured a tactic called village burning. It’s what it sounds like. His forces would encircle a Circassian village, loot it as best they could, kill any who attempted to flee past the Russian lines, then set the village and its inhabitants on fire. Tsitsianov lauded this as a way to “show how insignificant [Circassians] are compared to Russia”, but he was by no means the only military commander in the region to engage in village burning. One General Bulgakov was believed to have burned almost 300 Circassian villages, although the worst atrocities — because we’re not to the worst atrocities yet — were unquestionably at the hands of Colonel (later General) Grigory Zass, who established village burning, mass rape of Circassian women and children, and the bayonetting of pregnant women through their stomach as official tactics for the troops under his command. In communications with other Russian commanders, he bragged about how effectively he ordered his troops to slaughter civilians. At one point, he sent word to Circassian commander Jembulat Boletoqo that he was willing to discuss terms for peace, then had Boletoqo assassinated by a sniper on his way to the sham peace accord. He collected severed body parts as trophies, including Circassian heads, some of which he had cleaned and stored in a box under his bed and others he impaled on poles outside his command tent. Circassian culture memorializes Zass as something like the living embodiment of the devil, and… you know, I can’t really find fault with that.

As a later commander, General Aleksey Yermolov, stated, “We need the Circassian lands, but we don’t have any need of the Circassians themselves.” Accordingly, as the Russian front slowly pushed into mountainous Circassia, Russia citizens were encouraged to settle in the heavily depopulated areas left behind. In many cases, Russian settlements were built directly on the ruins of burned Circassian villages. The West helped seal the fate of Circassia in 1856 with the Treaty of Paris. Although British representative George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon, attempted to include assistance for Circassia in the treaty negotiations, those efforts came to naught (as an aside, you know it’s bad when the 19th-century British were concerned about a region’s native population); ultimately, the Treaty of Paris effectively provided international agreement that the Russian Empire was the legitimate ruler of Circassia.

Eventually, the Russian policy changed from outright extermination to mere expulsion (although there was still plenty of the former). Beginning in the 1860s, under the lead of then-Minister of War Dmitry Milyutin, mass expulsion of remaining Circassians to the Ottoman Empire began. The Circassians made a final, desperate plea for help from the West; Ottoman, French, and British leaders all agreed to recognize and support an independent Circassia if they could form a coherent state to recognize. Many of the Circassian tribal leaders fell back to Sochi. Yes, that’s the same modern resort-town Sochi that hosted the 2014 Winter Olympics. Now you know why there were protests over the selection of Sochi; “athletes are skiing on the bones of our ancestors”, as one Circassian activist described it. But, back in the 19th century, the Circassians did briefly establish a national parliament there. Then the Russians overrran Sochi, wiping out essentially its entire population, and that was basically that.

Russian and Ottoman leaders agreed on a treaty to allow the migration of some 50,000 Circassians, but Russian forces never intended to limit their efforts to merely 50,000. Deported populations were largely packed into ramshackle ships bound for the Ottoman Black Sea ports under conditions that would make a Triangle Trade slave-handler blanch. Many such ships sunk, and many others arrived with only corpses aboard. Outbreaks of disease were frequent among the poorly-clothed (and sometimes outright naked), malnourished refugees. The Ottoman Empire formally protested on the grounds that this was creating a humanitarian disaster (as another aside, you know it’s bad when the 19th-century Ottoman Empire complains about a humanitarian disaster); the Russians responded by increasing the rate of deportations. The Ottoman Navy ultimately got involved, pressing their war fleet into service as refugee transports in an effort to minimize the impact.

All in all, a population of perhaps 2 million ethnic Circassians in Circassia itself was reduced to fewer than 100,000. Many Circassian tribes were completely exterminated. Ottoman archives suggest that a million refugees entered their land, but that around half of them died on the beaches from injury, malnutrition, disease, and the rigors of the voyage. There is credible reason to believe that the Circassian genocide was the largest and worst genocide of the 19th century. Among the Circassians, it is known as Tsitsekun, a word adapted from the now-extinct Ubykh language formerly spoken in part of Circassia (around Sochi, ironically). Etymologically, it means something akin to “the killing of a people”, but Tevfik Esenç — the world’s last speaker of Ubykh — was asked what it meant to him. It was, he said, “a massacre so evil that only Satan could think of it”.

The Soviets shuffled the ruins of Circassia into several different administrative regions. There’s not much evidence that was done specifically to discourage unrest or erase the region’s legitimate cultural identity, but I think we can safely make the assumption that they had that in mind. Karachay-Cherkessia, in particular, lumps together Circassian land with the territory of the Turkic Karachay people, presumably in an effort to dilute the organizational power of both. In any case, ethnic conflict in Circassia has been much less of an issue than in, say, Chechnya or Dagestan, likely because there are simply fewer ethnic Circassians left. But there have been occasionally pushes for greater recognition of Circassia within the Soviet Union and, now, Russia. Some low-level unrest has occurred in Karachay-Cherkessia; I don’t know whether that’s affiliated with the Circassians or the Karachay (the official Russian line is that it was external influence by Chechen radicals, but if you buy that, I’ve got a bridge to sell you). On the other hand, the FSB did assassinate the Circassian head of the republic’s assembly (and his wife) in 2007, so… yeah.

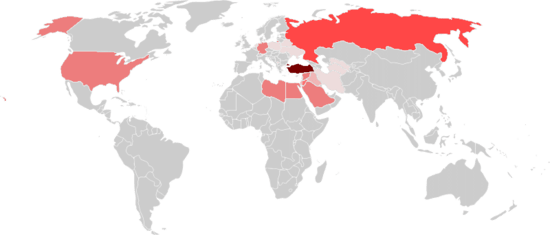

It’s safe to assume that the low overall population and large Russian ethnic presence here (Russians are now the ethnic majority in Adygea) would make this an unlikely place for all-out revolt. On the other hand, the Circassian diapora has had a significant impacts elsewhere. Ethnic Circassians were influential in the Turkish War of Independence. They have held significant military positions in Syria (before that happened), Libya, and Egypt. They literally founded the modern Jordanian capital of Amman. And among the wider Circassian population, a desire has emerged periodically to reclaim their homeland and receive recognition, if not reparations, for past crimes.

Is this region going to break for independence? Not today, certainly. But it’s certainly possible to image that, if the central Russian government’s hold over more restive regions were to fail amidst a wider collapse, that Circassia might — finally — end up emerging from the ashes.

EDIT: I did not expect a long block of history to make the Rec List. Thank you, everyone, for your interest in this!

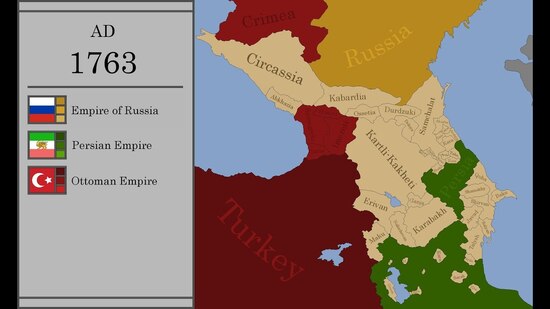

A couple of people requested a little broader map of the region. It’s difficult to find maps that focus on the Caucasus from an appropriate period in time to give a sense of history and scale here. A few Russian maps from the early 1800s have been made available online. But I do not speak Russian and am not particularly willing to take their maps at face value, even from before the Russo-Circassian War. I have occasional quibbles with Khey Pard’s History maps on Youtube, but this 1763 image from his History of the Caucasus: Every Year ought to at least give a little wider context. The body of the water to the left is the Black Sea (withe the Sea of Azov at extreme top-left); to the right, the Caspian.