Although Poles and members of the Circassian diaspora may seem as though they have little in common today, it was not always so. Perhaps one of the most unusual partnerships of the 19th century was born of the intense collaborative efforts of Poles and Circassians to free themselves from Russian domination. By this time Russian expansion had swallowed up most of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and threatened to engulf the homeland of the Circassian people in the northwest Caucasus. The machinations of stateless Poles in France, England, and the Ottoman Empire became a main source of support for the beleaguered Circassians during their protracted struggle against the Romanov state.

In their continued fight for national independence following the partition and dissolution of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at the end of the 18th century by Russia, Prussia, and Austria, Polish nationalists perceived that they were quite alone amongst the various minority populations of the Romanov Empire in their efforts to stage large-scale uprisings against Russian rule. In the early 1830s, however, Polish insurrectionists recognized that they shared common goals with the Circassian population of the Caucasus, which was in the throes of a prolonged armed resistance against Romanov expansion.

Historically, Circassian tribes were sometimes-clients of the Crimean Khanate, which was itself a part of the Ottoman Empire. Romanov expansion into the Caucasus beginning in the early 18th century onwards pushed the Circassian tribes to cooperate more closely with the Ottoman state. The defeat of Ottoman forces by Imperial Russia during the “Leh Seferi” (1768-1774 Russo-Turkish War) and the subsequent treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 awarded independence to the Crimean Khanate and the Northern Caucasus, which where annexed by the Romanovs in 1787. As a result, Circassia became a sort of front line for the Ottoman Empire in the north Caucasus around the same time that Poland-Lithuania began to be partitioned by its neighbors.

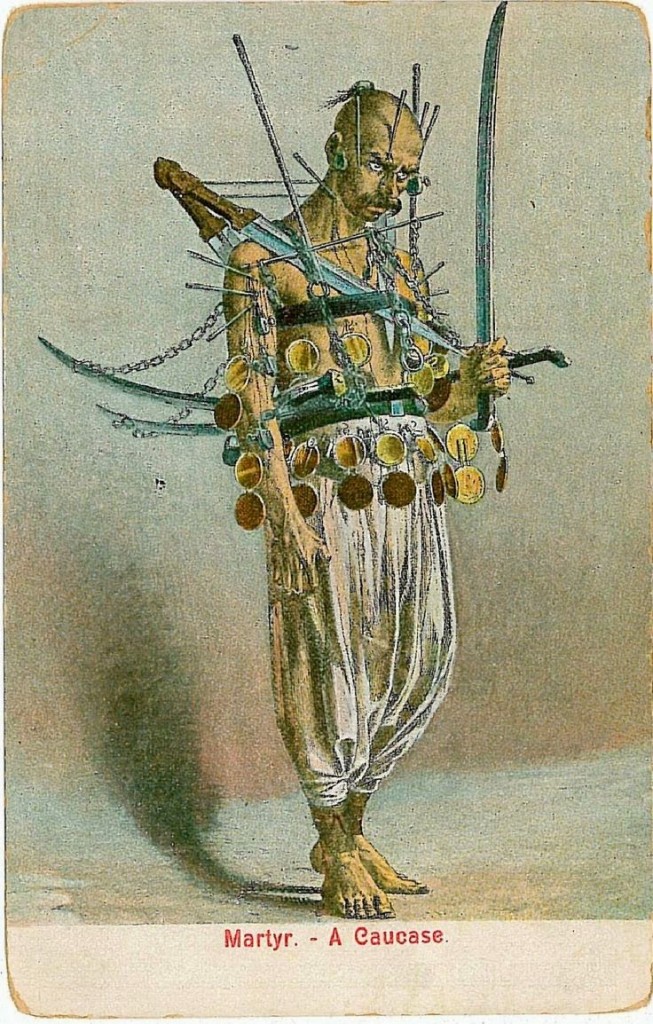

In the end, the Ottoman Empire was unable to keep pace with Imperial Russia, which built lines of fortifications along their Caucasian borders, settled large numbers of Cossacks in the region, and pushed into the southern Caucasus, annexing Georgia in 1801. Concurrent wars between Russia and Persia led to the extension of Romanov power into the Armenian plateau. Russia further consolidated its eastern Caucasian holdings with the treaty of Türkmençay in 1828 after taking Tabriz from ‘Abbas Mirza. The final blow came with the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, which forced the Ottomans to abandon their official claims to Circassia. Despite this, the Circassians managed to hold their ground against the Romanov army until 1864, at which point the bulk of the Circassian population was displaced or killed. It was during this prolonged period of resistance that Polish nationalists lent their support.

In the early 1830s Prince Adam Czartoryski, a key patron of the Wielka Emigracja (Great Emigration) of polish intelligentsia and nationalists from the defunct Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to the cultural and political centers of Paris, London, and Istanbul, sent the first Polish agents to meet with Circassian leaders in their alpine redoubts in the north Caucasus. Elements within the Polish expatriate leadership felt that a free Poland could rise from the smoking battlefields of a great war fought between the Western Powers and the Ottoman Empire against Russia, which controlled most of the former Commonwealth’s territories. The émigrés, therefore, were forced to walk a fine line between the pursuit of their own nationalist aspirations and keeping their French, English, and Ottoman protectors and sometimes-benefactors complacent.

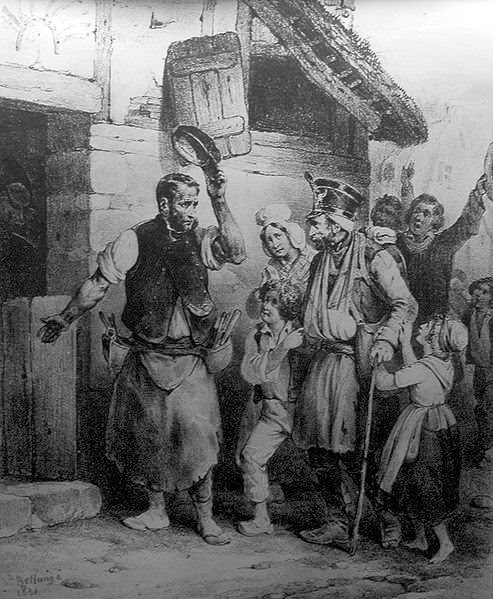

For thirty-odd years, numerous members of the Polish émigré community in Istanbul became involved in the Circassian cause by volunteering to fight directly alongside the Circassians, or by working to support their cause through diplomacy. The émigrés’ awareness of this issue was strengthened by the experiences of the many Poles who had been forced to serve in the Russian army in the Caucasus. Contemporary accounts of the treatment of Polish deserters and prisoners of war by the Circassian irregular military units are contradictory. It appears, however, that some Polish prisoners were incorporated directly into local guerilla units, and it was claimed that the Circassian Chief Şamil “always, want(ed) to have a host of Polish Ulans before him” (Lewak, 49). An important factor that led to the unlikely involvement of exiled Poles in the affairs of Circassian highlanders was the well-established tradition of the service of Polish Legions in extra-national conflicts. Over the years following the partitioning of Poland-Lithuania, Poles formed their own units and fought in the Napoleonic wars, Haitian Revolution, the 1848 revolutions that took place in Hungary and Italy, the Crimean War, and the American Civil War in conflicts that were politically or philosophically tied to the Polish cause.

In 1836, during the early phases of Polish-Circassian cooperation, the renegade secretary of the British Embassy in Istanbul, a man named David Urquhart, dispatched a British schooner that was filled with arms illegally bound for Circassian resistance forces. Russian forces seized the “Vixen” after it attempted to run a naval blockade and land its cargo on the Circassian coastline. The “Vixen Incident”, the result of a lone diplomat’s unsupported desire to help the Circassians, nearly caused a war between Britain and Russia. This would have served Polish purposes well and, in order to spread awareness of the event, Prince Czartoryski and his agent Władysław Zamojski attempted to bring the issue to the attention Western populaces by casting it in a favorable light in numerous publications disseminated to the British and French publics.

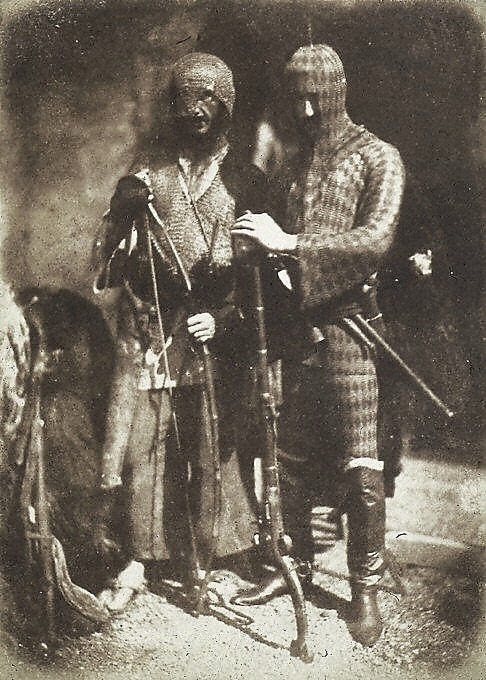

In addition to this, Prince Adam Czartoryski’s Hôtel Lambert and its Eastern Agency were involved in various attempts to create unity among the four main Circassian tribes, who they continued to fund and arm. Between 1841-1852 the Polish émigrés were the only significant source of foreign support for the Circassian rebels (Lewak, 52). This came to an end during the Crimean War when the Allied Powers of Britain and France began to view the Circassians as potential partners in their fight with Russia and briefly funded their resistance during the conflict. After the war, in 1857, an armed expedition led by Colonel Teofil Lapiński, which was manned almost exclusively by Polish émigrés, reached the beleaguered Circassians and fought a guerilla war at their side until 1860.

In 1858 Colonel Władysław Jordan was appointed by Prince Adam Czartoryski to be his new chief agent of the Eastern Agency. Through him, and his connections with the powerful Hôtel Lambert, Circassian leaders were able to petitioned for the aid of Queen Victoria and Napoleon III. When aid was refused, Czartoryski personally sponsored Circassian leaders in a trip to Paris and London in hopes that their physical presence would add weight to their pleas. Ultimately, it did not.

By the 1860s it began to look as though the remaining Circassian forces would succumb to Russian military superiority. The Hôtel Lambert rallied together the Polish émigré community of Istanbul and attempted to forestall this by petitioning France and England for their support of a joint Polish-Circassian “crusade” (Brock, 407). This call for action occurred just as the 1863 January uprising in the Congress Kingdom of Russian-controlled Poland was coming to a head. Lambert’s main source of support for the Polish/Circassian cause in England was the organizer of the disastrous “Vixen Incident”, David Urquhart, whose enthusiasm for the Circassian cause had not been dampened by a failed diplomatic career. Over the years he had continued to work closely with the Polish émigré community of Britain, making use of their direct contact with the Circassian forces. In their meetings with British officials, Hôtel Lambert agents attempted to cast Circassia as the breakwater upon which the wave of Russian expansion would smash itself to pieces before it could make its way into Persia and India. Although greater public awareness of the subject was achieved due to the work of the Urquhart and the Polish émigrés, the French and British governments refused to back either the Polish or Circassian causes.

In 1863 David Urquhart was involved in another risky scheme to send a boatload of goods to the Circassian coast in order to force Russia to recognize a pre-existent free trade agreement that was supposed to be in effect in that region. Instead of harmless trade goods, however, the “Chesapeake” would be full of illegal arms destined for Circassian forces. Władysław Zamoyski and Prince Adam Czartoryski’s son Władysław were amongst the primary benefactors of this ill-fated project. After a lifetime of espionage and secret dealings, Urquhart’s extreme paranoia caused him to accuse his fellow-conspirators of being “Russian spies”, which led to the breakdown of his relationship with Polish and Circassian leaders. As a result, he soon lost his place as a leading organizer in the scheme. The “Chesapeake Plan” was taken over by the Poles of the Hôtel Lambert.

When the ship arrived in Istanbul, it was loaded with a contingent of Polish soldiers who were meant to form the core of a new Polish Legion in Circassia. Similar to the Polish Legions in the Ottoman army during the Crimean War, their numbers were once again hoped to swell with Polish deserters from the Russian army. Klemens Przewłocki, who was a main organizer of Michał Czajkowski/Sadık Paşa’s Polish Cossack Legion in the Crimean War (“The Sultan’s Cossacks”), was given control of the unit. Przewłocki’s expedition to Circassia lasted only a few months after which famine and a lack of material support forced the Poles to retreat. The Hôtel Lambert had once again relied too heavily on Polish deserters from the Russian army to fill out the ranks of their Legions. Although they defeated Russian forces in various engagements, in the end their efforts were further hindered because the Ottoman government refused to reinforce the Circassian rebels. The capture of the key fort at Kbaada on 21 May, 1864 ended the Caucasian Wars. This, in turn, sparked the emigration of some 400,000 Circassians to the Ottoman Empire in the late 1860s and 1870s.

The Ottoman government turned a blind eye towards the involvement of its Polish émigré community in the external affairs of the Circassian insurrectionists. This attitude proved advantageous for the conspirators; it allowed the Poles to develop and execute numerous plans that were detrimental to Imperial Russia. Ultimately, the unwillingness of the Ottoman government to involve itself openly in the Caucasian Wars stemmed from a desire to avoid another conflict with Russia. By 1864 the influence of the Hôtel Lambert in European politics began to decline as the insurrectionary government responded to shifting political tides by abandoning their policy of seeking help from the English and French and realigned themselves with Hungarian and Italian revolutionary factions. As such, plans to regain Polish independence through direct intervention in the Caucasus were abandoned.

The overall effect that the Polish émigré community had on the Circassians’ struggle for survival may not have been monumental in scope, but the personal sacrifice of combatants and the political influence wielded by their Polish patrons abroad provided new lines of communication through which Circassians could forge relationships with the governments of the Western Powers. The result of these efforts was to keep the “Polish Question” alive amongst the Great Powers of Europe; the Circassians were not as fortunate.

Select Bibliography:

- Brock, Peter. 1956. “The fall of Circassia: A study in private diplomacy.” The English Historical Review 71, (280) (Jul.): 401-27.

- Dziewanowski, M. H. 1948. “1848 and the Hotel Lambert.” The Slavonic and East European Review 26, (67) (Apr.): 361-73.

- Lewak, Adam. 1935. Dzieje Emigracji Polskiej w Turcji, 1831-1878. Warszawa: Nak. Instytutu Wschodniego.

- Łątka, Jerzy S. 2005. Słownik Polaków w Imperium Osmańskim i Republice Turcji. Kraków: Księg. Akademicka.

- Kisluk, Eugene J. 2005. Brothers From the North: The Polish democratic society and the European revolutions of 1848-1849. New York: Columbia University Press.

Posted by:

Michael Połczyński is a Doctoral Candidate at Georgetown University. For more on the author see: https://georgetown.academia.edu/MichaelPołczyński

http://poloniaottomanica.blogspot.com/2014/03/eagles-in-caucasus-polish-circassian.html