Russian imperialism was never gone. We just stopped seeing it.

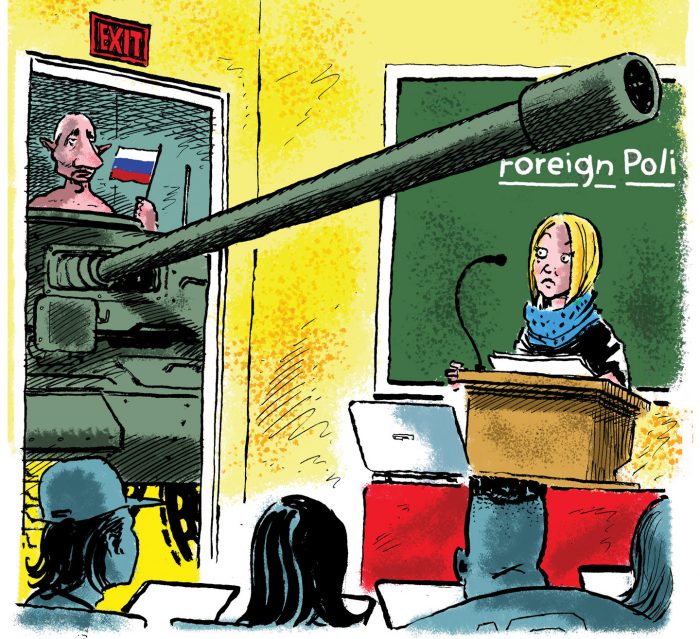

Understanding global politics is needed now more than ever

On the first day of class in fall 2017, my Russian politics class was packed. I was surprised to see 24 students in it, including most of the defensive backfield of the football team. Over the course of almost 30 years of teaching, I’ve noticed that Russia only becomes interesting to students when it makes the headlines of U.S. news. Otherwise, they forget about it. The same can be said of the American public.

Although it is the largest country in the world in terms of land mass, Russia has less than half the population of the United States and an economy equivalent to that of Texas. Unless it is directly affecting us, Russia scarcely makes a ripple in the consciousnesses of most Americans most of the time. Aside from the functions of our State Department and military, Americans are internationally notorious for our ethno-centric and isolationist stances with regard to the rest of the world. At Linfield University, I try to make sure students in my classes emerge with a more internationalist, less provincial view of the world as well as a sense of how important it is to have knowledge of foreign affairs. More specifically, I try to make sure they know something about Russia.

How important is Russia? It is true that it took a huge economic hit in the 1990s after the Soviet Union fell and communism became discredited as an alternative political system. All 15 union republics became separate sovereign states, including the Baltic states, Ukraine, Georgia and the five “stans” of Central Asia. As a result, Russia no longer had the power or prestige that it had enjoyed as the Soviet Union, the other superpower.

Americans perhaps understandably forgot about Russia in the 1990s. Pundits and experts told them it was evolving in a capitalist and democratic direction. And after 2001, they were preoccupied by the war on terror, to the extent that they thought about international relations at all. Francis Fukuyama triumphantly argued that the end of history had happened with the complete defeat of communism and the victory of classic liberalism as the only viable system in economics and politics. Russia was on the ropes and was struggling. Meanwhile, Americans paid very little attention to the two wars in Chechnya, an ethnic separatist province, in which Russian air power completely flattened its capital, Grozny, and installed a Chechen thug as leader. The second war in Chechnya occurred in 1999 and was engineered by Russian President Vladimir Putin, the newly anointed successor to Boris Yeltsin, to show his credentials as a strong Russian leader not afraid to use force.

We forget Russia at our peril. The Soviet Union’s fall is seen by Putin as the biggest catastrophe of the 20th century. This is saying something, since the Soviet Union lost approximately 20 million people during World War II, and Putin often uses that war as a symbol of Russian heroism and leading role in the world.

Chechnya should have been a clue. It is now abundantly clear that Putin plays the long game, and slowly he has built up Russian economic and military power with the ultimate goal of regaining Russian imperial dominance. We in the West were slow to see this. Chechnya was seen as an internal matter. Europe and the United States reacted with handwringing when Russia attacked Georgia (a former Soviet republic) in 2008, annexing territory populated by non-Georgian ethnic groups and Russian speakers. Ask most Americans if they have ever heard of Chechnya or Georgia. Nyet, they’d say.

After mass protests of a rigged election, Putin again came to presidential office in 2012. He was apparently surprised by the protests and became more active about ensuring his rule over the long term as well as in rebuilding Russia’s reputation as a serious world power. These two things are intertwined for him. For Putin, the kind of world power Russia should be is imperialist. It’s not the traditional kind of empire westerners think of when Europe had colonies all over the world. Rather, it’s a land empire that forms a buffer of non-Russian peoples and territories arrayed around the Russian heartland, an empire that Russia dominates politically, economically and culturally.

The events of 2014 that finally tipped Putin’s hand about his imperial ambitions were the seizing of Crimea and the military support given to “patriotic” separatist Russian speakers in two Ukrainian provinces, Donetsk and Luhansk. Sound familiar? That struggle was stalemated at relatively low levels of violence between Ukrainian and separatist forces until Feb. 24, 2022, when Russia undertook a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. As a scholar of Russia and Eastern Europe, I was completely appalled by this overt aggression. It has the potential to completely upend the status quo international order of the past 70 years, not to mention again change the map of Europe to the detriment of former Eastern bloc citizens. And yet, I was not surprised. Knowing Putin for what he is, an imperialist and an arch-realist in international relations, helps us understand his behavior.

Between 2014 and 2022, while Russia was building its strength, Putin has done everything possible to weaken European powers and the United States. Russia re-emerged in American consciousness in the presidential electoral campaign of 2016 through its machinations against Hillary Clinton, its army of bots impersonating real people whose anti-Clinton messages were reproduced millions of times and shared with millions of people. Putin’s IT trolls had pioneered similar disinformation campaigns previously in European elections. As Russian attempts to interfere in the U.S. election were revealed, Americans were caught off-guard. Hence, my large class of students in Russian politics the fall after the 2016 election – students who wanted to understand what was going on in Russia.

And now what was held by international relations practitioners and academic specialists to be unthinkable, since it violates the first principle of international law, has happened: Putin’s aggressive military invasion of Ukraine. Putin – as a realist – understands very well that military encroachment that violates another country’s sovereign borders contravenes the strongest international norms of state behavior dating back to the end of WW II. “No problem,” Putin believes. “We are just restoring what was already ours.” The war has not proceeded as Putin planned, since the capital of Kyiv was not taken in 48 hours with the Ukrainian leadership having fled or been killed, as he no doubt expected. The Ukrainian military has mounted a powerful resistance. The Ukrainian population has unified around its president and its national identity.

What instead has been demonstrated by the Russian invasion is a fatal shortcoming of autocratic rule: Putin’s belief in his own propaganda, not to mention ignoring the weaknesses of the much-vaunted and “reformed” Russian armed forces. Withdrawing from the Kyivan suburbs and other towns they had taken, Russian forces executed unarmed civilians on the streets. Evidence of thousands in mass graves have been found by war crimes investigators. “No matter,” Putin believes. “We will maintain that the Ukrainians themselves staged these killings.”

Despite his original deluded miscalculations, Putin has regrouped and is focusing on taking the whole of the Donbas territory in the east. True to form, not only military targets but population centers, hospitals and schools are being pulverized into rubble by Russia’s overwhelming heavy artillery capabilities. Putin has made clear that he will not stop until Russia annexes Donetsk and Luhansk, as well as other territory that connects to Crimea. There is no peace process or ceasefire in sight. Ukraine insists that it wants all the territory back that Russia has taken. The war looks set to grind on for months, if not years.

In the meantime, with the seeming inexorability of Putin’s plans for restoration of the Russian empire, the next logical question is whether the Baltic states, Moldova or even Poland are next targets. This would take international conflict to the next level, and a NATO response would be inevitable. What that response would be is not clear, although there seems to be more political will now for a strong, unified response than in the past. I hope that response does not bring about nuclear conflict, as Putin threatens, and I hope that when I teach Russian politics in spring 2023, my class again will be full. If not, it would most likely mean that Russia is out of the news, and we will be dismissing it, not seeing it and, once again, forgetting about it. Relentlessly, though, as long as Putin remains in power (technically until 2036), he will try to exert even more pressure, using force if necessary, to reconstruct the Russian empire as it existed both under the tsars and the Soviets.

As before, we forget about Russia at our peril.

Dawn Nowacki

Political science professor

Dawn Nowacki has been teaching at Linfield since 1994. She received a bachelor’s degree in Russian language and area studies and a master’s in international communication from the University of Washington. After working for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, she attended Emory University and received her Ph.D. in political science.

Nowacki was honored with a Fulbright Teaching Fellowship for Russia in 2001 and served as the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield. Her academic work includes articles and papers on the intersections of gender representation, religion and nationality in the politics of the former Soviet sphere and the Middle East.